'Six days before the Passover Jesus came to Bethany, the home of Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead. There they gave a dinner for him. Martha served, and Lazarus was one of those at the table with him. Mary took a pound of costly perfume made of pure nard, anointed Jesus' feet, and wiped them with her hair. The house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume. But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (the one who was about to betray him), said, "Why was this perfume not sold for three hundred denarii and the money given to the poor?" (He said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief; he kept the common purse and used to steal what was put into it.) Jesus said, "Leave her alone. She bought it so that she might keep it for the day of my burial. You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me."'

--John 12: 1-8

There are sayings in the Bible that are not always easy for us to hear. When these sayings come from the mouth of Jesus they are even more difficult, and one of the sayings of Jesus for which this is most true is the final line from our text today: "You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me."

Homeless Jesus

The question of how we deal with poverty is one with which people have wrestled for centuries. Sadly, the answer to that question so very often through history has been: we don’t. Traditionally, the needs of the poor have been neglected in order to meet the needs of the rich, and whenever poor folks have tried to rally together for change, they have been more often than not squashed by those in power. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King—whose feast day in our church was this past Thursday—was perhaps the loudest modern voice of the movement to not only address the needs of the poor but to deconstruct the systems that perpetuated this divide by empowering the poor and encouraging those of means to work WITH the poor for change, rather than treat them as a charity case. He once said: “A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies…True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.” He called this revolution a Poor People’s Campaign. If that sounds familiar, it’s because the movement of the same name being spear-headed by The Rev. Dr. William Barber right here in North Carolina is carrying on the legacy of King’s original.

For more information on the new Poor People's Campaign go to www.poorpeoplescampaign.org

Let’s be honest, though, restructuring those edifices and deconstructing those systems is a big, big task. Furthermore, we are too often tempted by that enormity to echo the words of Jesus as though we cannot—and maybe even should not—attempt to create a society where poverty is eradicated. Besides, even if we did try, it’s way too big; after all, Jesus himself says we will always have the poor with us, so why even bother? Everyone from pastors to government officials have quoted this phrase from Jesus and used it as proof that working to alleviate poverty on the whole—rather than just flinging a coin to a beggar from time to time—is neither a realistic goal nor something Jesus actually expects us to do. I would, with all Christian love, like to challenge such suggestions today and dare to offer that Jesus’ statement does, in fact, serve as a mandate for us to do all we can to not only address the needs of individuals who are living with poverty but also the systems that keep them there.

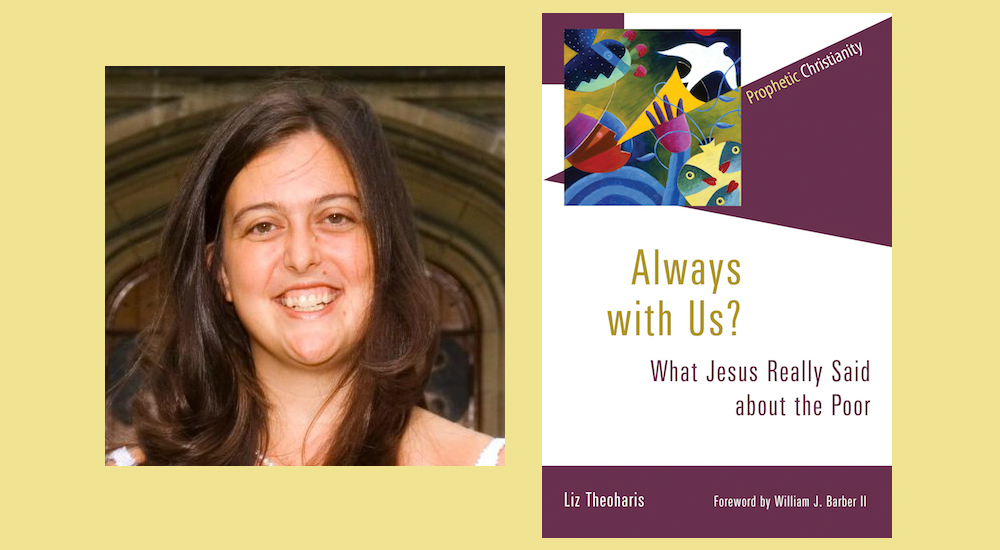

I do want to preface all of this by saying that much of the light that I intend to shed on this statement from Jesus comes from The Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis a Presbyterian pastor (and seminary colleague of my wife Kristen) and author of the book Always with Us? What Jesus Really Said About the Poor. In her book, Dr. Theoharis examines this story—which can also be found in each of the three other Gospels, in Matthew, chapter 25, Mark, chapter 14, and Luke, chapter 7—and she proposes that this entire story is itself a call for the followers of Jesus to care for the poor, rather than brush them off by referencing Jesus’ statement with the same flippancy of Judas.

The Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis and her new book, which can be purchased here.

So let’s dig into this story. First off, the meal to which Jesus has been invited is hosted by Mary, Martha, and Lazarus of Bethany, a town whose very name means, in Hebrew, “the house of the poor.” Right off the bat poverty is at the forefront of this encounter. It is here, in the midst of poverty, that Jesus is anointed—it’s his feet in John’s version and his head in the other versions. And what does Messiah mean in Hebrew?? Anointed one! It’s the people living with the everyday realities of poverty who recognize Jesus for who he is. It is one of them who anoints him, not a person of means. Mary’s action reinforces that Jesus has come to bring good news to the poor, and what’s more, to model for his own followers that they are to do the same in both word and action. This very model clashes with everything the people around him—including his disciples—know about wealth and power. Power flows from the wealthy, after all. It was true in their day, and it’s true in ours, but here the power to authorize Jesus’ Messiahship comes from the action of a poor person, not a wealthy one.

But what about Mary’s action? What she does isn’t in the slightest way frugal. Doesn’t it seem even a little wasteful to take that jar of nard—which was worth about a year’s amount of wages—and use all of it to anoint Jesus? In the other three Gospels the disciples as a whole chide Mary for this move—and point out that nard could've been sold and the money spent to help the poor —while in John it’s Judas who is named as the one doing the chiding—although John makes a point that Judas didn’t really care about the poor, effectively making him a scapegoat. We can, on some level understand the disciples’ response, though, can’t we? This poor person takes the one thing in her house that’s worth the most money, and instead of selling it and helping her siblings get by, she wastes it. Doesn’t that seem irresponsible?

Maybe to us, but that’s not the point. If it were Jesus would have addressed it, but if he anything he commends Mary's action. Here, then, is where Jesus’ words sometimes get twisted. We hear him say, “You will always have the poor with you,” and we are tempted to think that he is justifying poverty in his or any society. But to fully understand what’s going on we have to be aware of the fact that Jesus is quoting Deuteronomy, chapter 15. In that chapter Moses says to the people that there will never cease to be a day when the poor are not with them precisely because they have not followed God’s laws mandating that they always care for the poor in their land, both the citizen and the foreigner. Deuteronomy 15 is a call for the people to not just throw their money at the problem of poverty, but it is a commandment to organize their society around the jubilee—the regular practice of forgiving debts and restoring land to families. This is justice, not charity, and that is what God’s law called for God’s people to live by. Jesus’ disciples would have known this by his simple statement of “you will always have the poor with you.” He didn’t even need to finish the whole reference to Deuteronomy for them to get the point! As Dr. Theoharis herself puts it: “Jesus is suggesting that if the disciples and other concerned people continue to offer charity-based solutions, Band-Aid help, and superficial solace instead of social transformation with the poor at the helm, poverty will not cease.”

Jesus’ statement is not a denouncement of the poor, nor is it an invitation for us to ignore the needs of the poor when we encounter them. We must never forget that, as God is not only aligned with the poor throughout the Hebrew Scriptures but is present in and of the poor in the person of Jesus himself. When we see the poor, we see Jesus, we see God. But the temptation is so often there for us to toss our money toward the individual and feel like we did our part. This is the perspective of the disciples. This is what they suggest be done with the nard, sell it and use the money to do, well, something. Jesus, however, by quoting Deuteronomy, makes it clear that it is about more than throwing money at a problem. It is about coming together to create a society where rich and poor are outmoded concepts, confined to a bygone era where power was top-down. The dream of Jesus is something that we see lived out later in the Acts of the Apostles, where, following his death, the believers finally got it. They held no debts toward each other—echoing the jubilee model from Deuteronomy—and there was no such thing as private possessions and wealth among them. It took a while, but the folks we often call the early Church understood that being a Christian was about not only praising Jesus but, in tangible ways, continuing his work of planting the seeds and tilling the soil for the Kingdom to grow.

Each of us, in our own way, can be more attuned to the systemic issues at play when we address the concerns of poverty. It’s not an either/or of whether we should help individuals versus address those systems. It's a both/and. That’s what Jesus is getting at when he denounces Judas’ flippant gripe. That is the revolutionary work that is before us, work grounded in equality and justice, rather than mere tolerance and charity. We can ask ourselves what actions we can take that are longer-lasting and more impactful. We can, instead of criticizing the poor person who we think is being irresponsible with her money and possessions, ask how she got into her position in the first place and wonder what Jesus would say and do about that, and respond in kind. We can pay attention and hear Jesus’ words not as an excuse for complacency but as an invitation to create a society where, in fact, Jesus IS always with us because our hearts, our minds, and our hands and feet are always positioned toward Jesus, toward those in need, working with them, and with the living Christ in our midst to alleviate poverty and injustice and establish the kingdom on earth as it is in heaven. That, to borrow the words of Saint Paul, is how we will know Christ and make him known.